Most Popular Artworks at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The best paintings at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Check out our guide to the best pieces on view right now at the world-renowned Museum of Modernistic Art in NYC

Among NYC'south art museums, MoMA'south collection of 20th-century artworks is arguably unrivaled among other holdings, like those of The Metropolitan Museum Of Art or the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. MoMA, later on all, has "Modern Fine art" right in its proper name, and beginning in 1929, it pioneered the acquisitions of masterpieces in Postimpressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and abstraction—not to mention Pop Fine art and works by leading contemporary artists. Though MoMA possesses works in all mediums, its horde of paintings takes eye phase in its collection, as you can meet in our listing of the best paintings at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

RECOMMENDED: A total guide to the Museum of Modern Art

Best paintings at the Museum of Modern Art

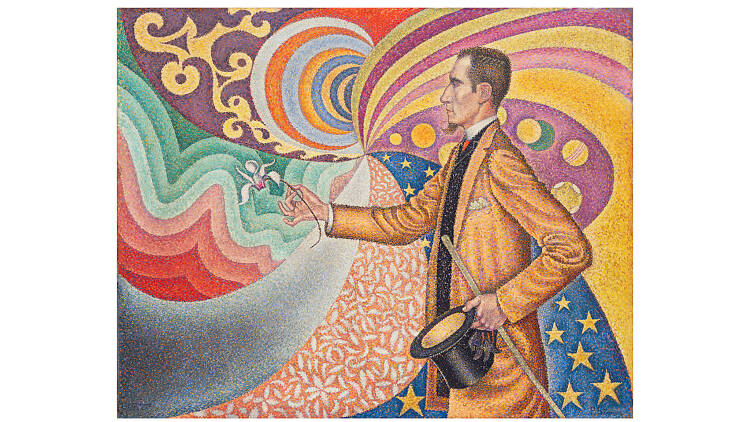

1. Lee Bontecou, Untitled (1961)

In the macho scene of postwar American art, Bontecou was a rare female presence, but when it came to making tough work, she could keep up with the boys and then some. This piece is made with industrial canvass salvaged from a conveyor belt that had been tossed out on the street by a laundry located below the artist'due south East Village apartment. The glowering form—suggesting a wormhole into some dimension of Cold State of war terror, or an eyepiece from a gas mask—was achieved past stretching material across a steel frame.

ii. Salvador Dalì, The Persistence of Retentivity (1931)

Dalì described his meticulously rendered works as "paw-painted dream photographs," and certainly, the melted watches that make their appearance in this Surrealist masterpiece have become familiar symbols of that moment when reverie seems to uncannily invade the everyday. The coast of the creative person's native Catalonia serves as the properties for this landscape of time, in which infinity and decay are held in equipoise. As for the odd rubbery animate being in the center of the limerick, it is the artist himself, or rather his profile, stretched and flattened like Silly Putty.

3. Willem de Kooning, Woman I (1950–52)

In the signature painting of De Kooning's career, the artist jokingly inserts an interplay between enormous eyes and breasts (strapped down hither as if they might burst from the picture aeroplane and smother the viewer), taunting us with the question, which would yous look at beginning? The flurry of fierce marks defining the figure could be easily read equally misogynistic, but complaining nearly misogyny in New York's postwar art earth is a bit like complaining that Rembrandt didn't take electric lights. With her verticality and frontal positioning, /Woman I/ seems enthroned: the regent of De Kooning's imagination.

4. Frida Kahlo, Cocky-Portrait with Cropped Pilus (1940)

This gender-bending self-portrait by the celebrated Mexican artist and feminist icon was occasioned by her divorce from Diego Rivera—the muralist notable non only for his own creative genius, but for his philandering ways. Kahlo had apparently enough of the latter, but as the painting indicates, she couldn't quite quit Rivera. She pictures herself in a chair, pilus shorn, with her signature peasant blouse and brim replaced by Rivera's clothes—effectively transforming herself into her ex-husband'south likeness. Her locks, now scattered across the floor, seem to writhe menacingly around her, and she captioned the composition with the words from a popular Mexican dear song: "Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don't dearest you anymore." Unsurprisingly, Kahlo remarried Rivera the following year, so this weirdly compelling painting could also exist described as a monument to codependency.

5. Roy Lichtenstein, Drowning Daughter (1963)

Lichtenstein'south Pop icon is at once a coolly ironic deconstruction of lurid melodrama and a formally dynamic—fifty-fifty moving—composition, thank you largely to the interplay of the discipline's hair (swept into a perfect Mad Men–era coif) and the waves (which seem to have wandered in from a Hokusai print) threatening her. The prototype, a crop from a panel in an early-'60s comic book titled Run for Dearest!, shows that Lichtenstein's in full command of his style, employing not only by his well-known Ben-Day dots, but as well bold blackness lines corralling areas of deep bluish. It'south a complete stunner.

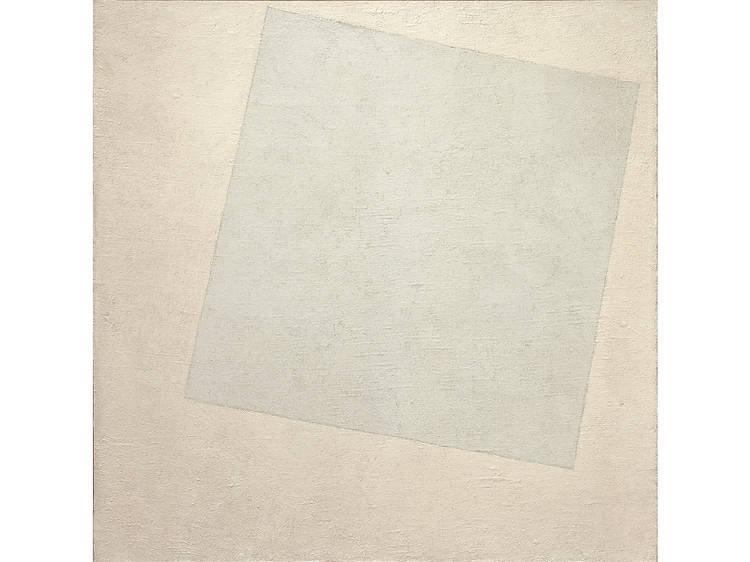

6. Kazimir Malevich, White on White (1918)

Though it was painted nearly a century agone, this painting'south radical nature continues to amaze. Malevich's aim wasn't pure reductivism, though. Inspired past Russia's icon tradition, the early on Soviet avant-gardist believed that the Russian Revolution had ushered in a new historic period in which materialism would give way to spirituality. He called his philosophy Suprematism, and /White on White/ serves as the supreme manifestation of the artist reaching for transcendence.

vii. Henri Matisse, The Piano Lesson (1916)

1 of the creative person'south almost personal pieces, The Pianoforte Lesson shows Matisse'due south son Pierre at the keyboard. Information technology'south a composition about infinite, but besides about time, as it echoes again and over again the pyramidal shape of the metronome on the pianoforte—in the band of green slicing beyond a casement to the left, and in the shadow falling across Pierre's confront. He is set between two of his father's works depicting females, the matronly Woman on a High Stool and a small sculpture of a sensuous, reclining nude. More than a simple description of a family life, The Piano Lesson serves as a meditation on manhood, and one boy'due south impending introduction to it.

8. Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907)

The ur-canvas of 20th-century art, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon ushered in the modernistic era past decisively breaking with the representational tradition of Western painting, incorporating allusions to the African masks that Picasso had seen in Paris's ethnographic museum at the Palais du Trocadro. It'southward compositional Deoxyribonucleic acid also includes El Greco'south The Vision of Saint John (1608–14), now hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. The women being intruded upon by the small withal-life at the lesser of frame are actually prostitutes in a brothel. An early study for the painting featured a medical student entering from the left to make his pick for the dark, but Picasso wisely decided to exit him out in the terminal composition, leaving only Avignon in the title as a clue to his subject area's origin: It'due south the proper noun of a street in the creative person'due south native Barcelona, famous for its cathouses.

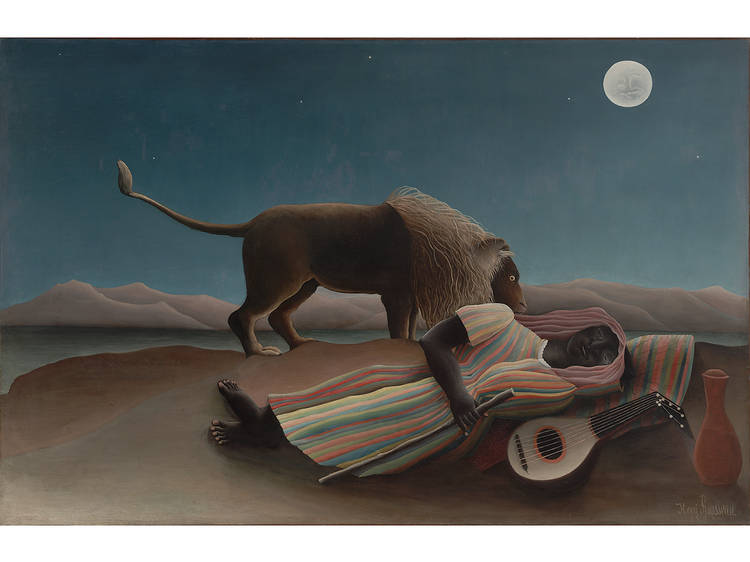

9. Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy (1897)

Rousseau's career represents the first instance, perchance, of a self-taught outsider artist who won the admiration of insider peers, though the road to recognition wasn't easy. The story goes that Picasso commencement stumbled upon the piece of work of this toll-collector-turned-painter while information technology was being sold on the sidewalk as used canvass to exist painted over. Since and so, Rousseau'southward mix of dreamy naive figuration and exotic landscapes (all imagined; he never left France) has become enduring—never more then than in this painting, in which the juxtaposition of beauty and beast has an unearthly quality.

10. Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Probably Van Gogh's nearly famous and popular painting, The Starry Night has inspired, amid other things, a treacly 1971 ballad by the musician Don McClean. For nearly people, the swirling, cyclonic tone of the painting is a straight reflection of Van Gogh'south reputation as a turbulent soul. Indeed, he painted the scene while he was a patient at the Saint-Paul mental asylum in Saint-Rémy, where he sought treatment for low and hallucinations.

11. James Ensor, Masks Confronting Death, 1888

Known for paintings featuring masks and skulls, the Belgian artist James Ensor is often seen as a forerunner of Surrealism, which is true up to a bespeak. Though seemingly Surreal in the broad sense of the term, his work wasn't concerned with dreams or the unconscious (which would afterward become Surrealist obsessions), only rather with the futility and irony of being. Furthermore, his themes were rooted in direct observation, as the ghouls and goblins that populate his imagery didn't spring from his imagination, but were based instead on props and costumes set up in his studio (a legacy of the family unit business organisation, a pocket-sized emporium that sold festive get-ups and souvenirs to tourists who came to Ensor's seaside hometown of Ostend for its annual Mardi Gras–style carnival). Such a tableau is featured in this painting where the key figure, representing decease, is actually a skull plopped on an arrangement of empty clothes. The same goes for the masked subjects crowding around grim reaper, who wears an elaborate lady's hat, giving the scene an unnerving erotic undertone.

12. Andy Warhol, Gold Marilyn Monroe (1962)

No Warhol demonstrates the creative person's worship of glamour better than this painting, created the twelvemonth Monroe died in an apparent suicide. It is the altarpiece in Andy's Pop Art church building of celebrity. But by the same token, the piece of work also speaks to Warhol'southward background equally an observant Catholic; it wouldn't expect all that out of identify at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome or at St. Patrick'southward Cathedral on Fifth Artery, where Warhol regularly attended mass (sans wig). The image is based on a publicity yet for the film Niagara, in which Monroe played opposite Joseph Cotton equally an unhappily married woman, plotting the murder of her husband.

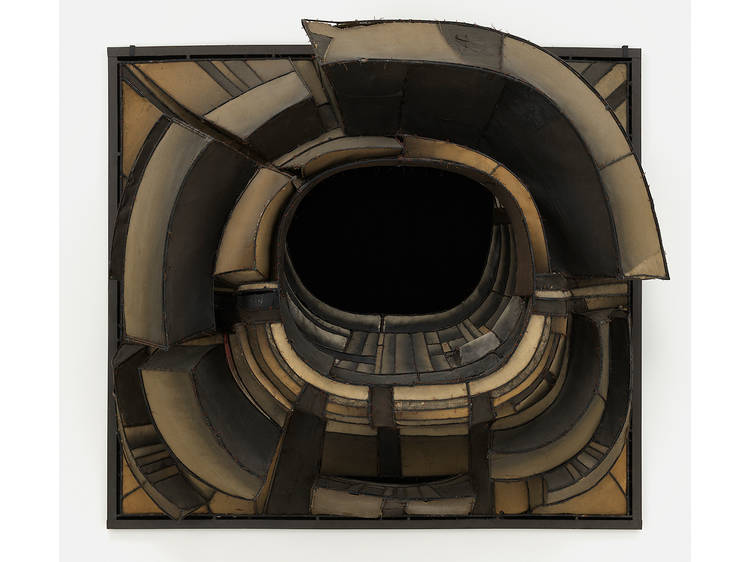

13. Paul Signac, Opus 217. Confronting the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of Chiliad. Félix Fénéon in 1890, 1890

Near the end of the 19th century, Impressionism's spontaneous mode of painting gave way to Postimpressionism and its more than methodical forms of expression. It was in this context that Pointillism emerged, and while usually associated with Georges Seurat, Paul Signac was another major figure of the movement. His best-known piece of work is this exuberant—almost psychedelic—portrait of his friend, Felix Fénéon. An fine art dealer and critic, Fénéon is seen posed in profile against an abstract, spiral background that symbolically sets in motion the theories of Charles Henry—a mathematician, inventor and aesthete who took a scientific view of colors, proposing that rather than being blended, different hues should be treated every bit pure independent elements and kept separate from one some other. His ideas underpinned Pointillism's technique of applying pigment as dabs of pure color that would mix in the eye of the viewer. Signac pays homage to Henry, while the painting's long, grandiose title seems to spoof his empirical claims for art. Fénéon, meanwhile is portrayed equally a magician, who, peak lid and cane in hand, brandishes a white bloom from which the pinwheel backdrop seems to emerge.

An electronic mail you'll actually love

🙌 Crawly, you're subscribed!

Thanks for subscribing! Expect out for your first newsletter in your inbox soon!

Source: https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/slideshow-top-20-paintings-at-moma

0 Response to "Most Popular Artworks at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art"

Post a Comment