Reviews of Small to Medium Sized Manufacturing Enterprises Usa

Abstract

The shine running of small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) presents a significant challenge irrespective of the technological and human resources they may have at their disposal. SMEs continuously encounter daily internal and external undesirable events and unwanted setbacks to their operations that detract from their business performance. These are referred to every bit 'disturbances' in our research study. Among the disturbances, some are probable to create risks to the enterprises in terms of loss of production, manufacturing capability, human being resources, market share, and, of grade, economic losses. These are finally referred to as 'hazard determinant' on the ground of their correlation with some risk indicators, which are linked to operational, occupational, and economic risks. To deal with these risk determinants effectively, SMEs need a systematic method of approach to identify and treat their potential effects along with an appropriate set of tools. Yet, initially, a strategic approach is required to identify typical take a chance determinants and their linkage with potential concern risks. In this connection, we conducted this report to explore the answer to the inquiry question: what are the typical chance determinants encountered by SMEs? We carried out an empirical investigation with a multi-method research approach (a combination of a questionnaire-based mail survey involving 212 SMEs and 5 in-depth case studies) in New Zealand. This paper presents a ready of typical internal and external risk determinants, which need special attention to be dealt with to minimize operational risks of an SME.

Background

In the dynamic and highly competitive business organisation environment, manufacturing industries are nether tremendous pressure due to the complimentary market economy, rapid technological development, and continuous changes in client demands (Islam et al. [2006]). To cope with the current business concern trends, the demands on modern manufacturing systems take required increased flexibility, college quality standards, and college innovative capacities (Monica and John [1999]). 'These demands emphasize the demand for loftier levels of overall system reliability that include the reliability of all human elements, machines, equipment, cloth treatment systems and other value added processes and management functions throughout the manufacturing system' (Islam et al. [2006]). Whatever the resources they possess, the manufacturing organizations encounter undesirable events and unwanted setbacks such as car breakdowns, textile shortages, accidents, and absenteeism that make the system unreliable and inconsistent (Monica and John [1999]; Islam [2008]; Islam et al. [2008]; Mitala and Pennathurb [2004]; Monostori et al. [1998]; Toulouse [2002]). In fact, undesirable events and unwanted setbacks (internal and external) in day-to-24-hour interval operations are common in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs; Islam [2008]). The authors of this paper chose the word 'disturbance' to represent any of these undesirable events and setbacks. They ascertain the disturbance equally 'an undesirable or unplanned upshot that causes the deviation of system functioning in such a way that it incurs a loss,' and the definition is published by the authors elsewhere (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam [2008]). This research adopts the definition of disturbance. Equally a disturbance creates undesirable consequences that are evidently detrimental to a business organization functioning, we finally refer to a disturbance as a 'risk determinant' on the ground of its significant presence in the system and its consequential negative impact on business organization and operational performance. Disturbances are linked to undesirable consequences which may originate from different circumstances (Monostori et al. [1998]). 'Whatever the sources of disturbances, the consequences resulting from them could be; difficulties to continue work, decreased productivity, reduced product rate, increased lacking products, unplanned rework, delayed delivery to market, unexpected downtime, man loss, etc.' (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam [2008]). In practise, in that location is a fiscal loss due to any consequential furnishings of disturbances. The combined issue of unlike disturbances could effectively cripple an SME's concern performance which may ultimately put it at risk of consummate failure (Islam et al. [2006]). The risks can, in general, be categorized into three groups: operational, occupational, or economic. The first category of risks involves the loss of production and the loss of production capability that includes productivity losses, quality-related losses, interrelated activity losses, and nugget losses. The second category comprises the risks associated with employees' health, condom, and well-being, while the 3rd category encompasses concern risks associated with the financial penalties resulting from either of the offset two categories likewise as compensation claims and damage to reputation. While dealing with risks, the term 'hazard' automatically comes into the scenario; thus, the definition of a adventure can play an of import role when dealing with risks in the industrial context. A hazard is a condition that can cause harm, injury, death, damage, or loss of equipment or personnel (Bahr [1997]) and can exist without anything really failing inside the enterprise. There are four types of hazards, namely catastrophic (expiry or serious personnel injury or loss of a complete system), critical (severe injury or loss of valuable equipment), minor (small-scale injury or modest system damage), and negligible (no resulting significant injury or organization impairment). While examining the definitions of a gamble, it can be noticed that a run a risk ultimately represents a situation or condition that has the potential to harm people, belongings, or the environment. All the same, a question now presents itself, that if at that place is no run a risk to harm any of these iii elements (people, property, surroundings), tin can we classify the situation as a take a chance? For an example, the absence of a cardinal machine operator may have no touch on any of these three elements, but it has the potential to develop financial risk to the organization in terms of loss of production; still, the bear upon might exist severe for a minor business if the absence is prolonged. There might exist some contend every bit to whether absenteeism should exist included in the hazard category or non, but most people would agree to recognize it every bit a potential operational disturbance which could have serious consequences for an SME. Operational disturbances can be seen from different perspectives and can likewise be described with various words such as disruptions, failures, errors, defects, losses, and waste material (Islam [2008]). Still, all potential disturbances and their consequential losses should be considered in the gamble management of SMEs because they can be both fourth dimension-consuming and costly. We believe that this type of disturbance should be studied under the umbrella of risk management. Consequently, while studying risk management in SMEs, nosotros prefer to use the term 'disturbance' instead of hazard. According to our definition, therefore, a disturbance represents all types of hazards as well any other unwanted setback that can produce uncertainty or a loss for an organization.

The focus of our research was to place typical gamble determinants of SMEs that need to exist considered in developing an integrated risk direction approach which should include strategic, operational, occupational, fiscal, and technology-oriented risks. The research is, therefore, built in a specific research question - what are the typical risk determinants of manufacturing SMEs?

Based on the findings related to the question, we have identified a ready of key internal and external operational disturbances, which are eventually highlighted equally 'chance determinants' based on their occurrence and consequential furnishings on the business performance of SMEs. This paper presents the identified risk determinants and describes a methodology to identify them.

SMEs are viewed every bit a source of flexibility and innovation, and they make significant contributions to the economies of many countries, both in terms of the number of SMEs and the proportion of the labor strength employed by them (Hoffman et al. [1998]; Ministry of Economic Development [2004]). However, SMEs are perceived as loftier-risk ventures, and the entry and get out rates support this perception (Zacharakis et al. [1999]). Previous inquiry has indicated that there is petty difference between small business concern failure rates in developed and developing economies, and it is estimated that 50% of all start-ups fail in their first yr, while 75% to 80% neglect inside the first 3 to 5 years in the USA (Anderson and Dunkelberg [1990]). It has also been shown that up to 50% of the modest businesses started in South Africa eventually failed (Watson and Vuuren [2002]). In New Zealand, xl% to l% of small businesses failed inside the beginning 10 years, and a negative correlation was found betwixt a firm'southward total full-time employment and its failure rate (Ministry of Economic Development [2004]). Business failure is frequently acquired by a lack of knowledge, misplaced overconfidence, lack of fiscal functioning strategies, or a lack of internal management planning (Gibson and Cassar [2005]; Hartcher et al. [2003]). In spite of high failure rates, however, small-scale businesses keep to be an essential component of the economic system of many countries as they account for a significant percentage of all entities and collectively use large numbers of the workforce. Mostly, SMEs depend on financial factors such equally profit or sales when considering business risks (Waring and Glendon [1998]). Yet, monetary factors alone may ignore many problems affecting the long-term reputation of the SME and its staff. A recent research written report has suggested that risk direction is less well developed within SMEs where the strong enterprise culture sometimes mitigates against managing risks in a professional person structured way (Virdi [2005]). According to the report, the SMEs are reluctant to adopt a formal risk management strategy despite having the testify that businesses that adopt risk management strategies are more likely to survive and grow. Zacharakis et al. ([1999]) identify some reasons for failures of small businesses that include both internal and external causes. The internal causes of failure include poor management, lack of risk direction planning, and failure to adopt a risk limit threshold. The external causes included government policies, the vulnerability resulting from pocket-size size, contest from larger businesses, civil strife, natural disasters, and full general economic downturns. It was also plant that 'overconfidence' could often bulldoze small-scale business operators to devalue the importance of cardinal take chances cess that ultimately caused their failure. Although at that place are some other causes for failure that are highlighted in this section, our enquiry is not intended to investigate the reasons behind the absolute failures of SMEs. Rather, it deals with identifying the potential risks existing when operating SMEs within their current infrastructures and then that they can avert potential failures past implementing a strategic risk direction arroyo. Because manufacturing involves a complicated mix of people, systems, processes, and equipment, an effective research strategy needs to be multidisciplinary in its approach to establishing a chance management framework (Islam [2008]). Because of some infrastructural, technological, financial, and human resource-related limitations, SMEs may continue themselves abroad from adopting a positive arroyo towards strategic risk management (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam [2008]; Hartcher et al. [2003]; Martie-Louise [2006]). Islam et al. ([2006]) country:

It is noteworthy to mention that major accidents and emergencies rarely occur in SMEs although minor losses, near misses, unsafe acts and unsafe conditions are common occurrences. But, bug, failures and mistakes as well as wrong or ineffective actions, are very likely occurrences in the daily business of SMEs and for this reason, in practice, modest incidents and well-nigh misses are worth analyzing since in slightly unlike circumstances the consequences could have been quite serious. By monitoring even pocket-size issues and analyzing their underlying causes, it might exist possible to discover causes for more serious issues and the existence of hazards. Therefore, no disturbance should be overlooked or should be allowed to happen over again.

In the authors' noesis, enquiry works done on risk direction take generally focused on particular industries such as nuclear, aviation, space exploration, chemic processing, and other areas where the consequence of a organization breakup is considered severe or catastrophic for human beings or the environment, and/or where the potential financial loss is pregnant (Islam et al. [2006]; Andrews and Moss [2002]; Khan and Abbasi [1998]; Milan [2000]; Seastroma et al. [2004]; Strupczewski [2003]). In improver, enquiry works on take a chance direction in other areas, including financial sectors, medical science, transportation, and structure engineering, take as well significantly expanded with time (Islam et al. [2006]). In contrast to this, lower priority has been noticed in the literature concerning risk management in the SME sector. Nigh of the studies relevant to risk management in this sector indeed concentrate solely on the risks associated with safety and occupational health (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam [2008]). Protective practices such as occupational safe and health and other safety-related programs should, if properly implemented and skillful, ensure meliorate health and working environments inside organizations. They exercise non, still, ensure the smooth running of the organization or minimize its risks operationally, technically, and/or financially.

Hazard identification inside a organisation is the starting betoken of whatever run a risk identification or cess process that emphasizes the critical components or factors that produce or could produce failure or harmful consequences for humans, assets, or the environment (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam [2008]). In this context, different techniques such equally Hazard and Operability Analysis studies, Failure Way and Consequence Analysis, Failure Mode and Effect Critical Analysis, Hazard Analysis with Critical Command Points, Fault Tree Analysis, Event Tree Analysis, 'What if' analysis, and Checklists are widely used in practice (Islam et al. [2006]; Khan and Abbasi [1998]; Mushtaq and Chung [2000]; Pearson and Dutson [1995]; Tixier et al. [2002]). All these techniques focus on the main hazard sources systematically, but none of them tin produce a thorough list of important organization failures, causes, consequences, and controls and can lend themselves to rigorous take a chance acceptability analysis (Islam et al. [2006]). Furthermore, none of the techniques are necessarily effective in identifying and prioritizing the risks associated with multifaceted criteria. None of the abovementioned methods alone can readily be applicable for dealing with risks associated with operational disturbances, because of their circuitous nature. 'For example, a disturbance such every bit 'tool shortage' could exist rooted in; erroneous planning of stock, misuse by the operator, unexpected breakage, or incorrect selection of tool for the particular task. Thus, the origin of the disturbance could either be strategic, operational or technical. This means that a detailed analysis of a particular disturbance is required to found a suitable hazard handling process' (Islam et al. [2006]). In this connection, we have adult a strategic risk direction model for SMEs and have published the model elsewhere (Islam et al. [2006]; Islam et al. [2008]). However, we conducted farther report on the identification of specific risk determinants of SMEs and have discussed the identified determinates in this paper.

Instance description

Research methodology

We choose an empirical investigation as it puts special emphasis on the affiliated research leading to the development of a strategic risk management framework in terms of operational and organizational aspects (Islam [2008]; Glaser and Strauss [1980]; Luis et al. [1999]; Mills et al. [1995]; Pettigrew et al. [1989]). The empirical investigation was carried out past applying a multi-method approach (combination of case written report and survey methods), called triangulation, which provided a relatively potent means of assessing the degree of convergence, besides as identifying divergences, between the results obtained (Islam [2008]; Brewer and Hunter [2006]; Jick [1979]). In the triangulation method, the survey results improved the authors' understanding of the particular phenomenon (human relationship betwixt potential disturbances and their associated risks in this case). On the other hand, the case studies added to a more holistic and richer contextual understanding of the survey results. Thus, the multi-method approach is believed to be enhancing the brownie of the research results while reducing the take chances of observations reflecting some unique artifact (Brewer and Hunter [2006]; Denzin [1989]).

Data drove methods and sample

For the empirical investigation, standard questionnaires were developed and verified by a panel of academic experts and after past an industry focus group in a airplane pilot study. The questionnaires were designed to explore the risk determinants (potential disturbances) and risk indicators (detrimental parameters to business concern operation) relating to existing practices in the studied organizations. The focal points of the questionnaire were (i) product-related activities associated with risks; (2) quality, reliability, and health- and safety-related bug of both avails and personnel; (iii) major activities in the supply chain networks; and finally, (4) strategic bug relating to the current practices in run a risk direction.

At that place were two phases in the data collection procedure. In the first stage, questionnaires were sent to 55 manufacturing SMEs (to 165 individual management personnel, to three tiers of direction of each organization), and in the second, to 157 SMEs (to 417 direction personnel). The respondents were given i calendar month to return the completed questionnaires while an additional 3 weeks were allocated for telephoning and personal interviewing to learn missing information in incomplete questionnaires. Out of 212 SMEs, 11 SMEs declined to participate in the questionnaire survey due to their organizational restructuring, busy scheduling of the management, absorption in other concern sectors, or some other undisclosed reasons, though they mentioned their keen interest (in the response letters) to the research subject. Iv sets of questionnaires were sent back to the researchers not finding the leaseholder. Five participating organizations provided partially completed questionnaires, which have been excluded in the analysis. Birthday, 96 usable responses from management personnel (top, middle, and front end-line management), from 32 responding SMEs, were returned and accept been analyzed, and presented in this newspaper. It is noted that the system which returned three sets of completed questionnaire is merely considered as responding SME. In this connection, the useful response charge per unit of eighteen.27% from companies was considered satisfactory and representative of SMEs in New Zealand. The overall response rate of 23.08% from the selected SMEs indicates the substantial importance of the research topic, while past experience suggests that mail survey response rates are often depression and appear to exist declining amid pocket-size business populations (Dennis [2003]). However, before making whatever conclusive remarks on the survey findings, further verification was carried out by subsequent in-depth case studies involving five SMEs from amongst the participants in the mail survey. We cull the follow-upwards case study approach as '…an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context and a methodology involving multiple sources of data which provides the fullest understanding of the phenomenon and improves the validity of research implications through triangulation' (Scudder and Hill [1998]; Yin [1994]). The case studies were conducted longitudinally over an 8-month period. The findings from the mail survey enabled us to develop a deeper understanding of the existing strategies and underlying practices in typical SMEs in New Zealand. During the example studies, ten elements of the performance, namely premises production purchasing people procedures protection processes performance planning, and policy, that stand for the main risk areas to the success of a concern were considered (Jeynes [2002]). An ethnographic approach, which involves the sustained participation in, and observation of, the applied business concern settings which cover the twenty-four hour period-to-day incidents and practical phenomena occurring within the organization, was applied in the example studies (Yin [1994]; Bowman and Ambrosini [1997]; Charmaz [2006]). Apart from direct observation, relevant documents and diagrams from the studied organizations were reviewed and verified. Supplementary information were nerveless through formal interviews (with primal senior executives who shape the firms' operations strategy) and informal discussions (with frontline managers, production supervisors, and some key employees on the shop-floor).

Validation of questionnaire

The mailed survey was carried out by the developed questionnaires. One questionnaire was designed for top management (senior executives), and the other was designed for center and front end-line management of each arrangement. The purpose of two divide questionnaires was to collect disturbance information from dissimilar areas of concerns of each management level. In full, 26 questions were formulated for the questionnaire of the peak management and 34 questions were in the questionnaire for middle direction. Even so, in the context of this paper, the questions that were directly related to the disturbances are presented in Additional file 1 for the clarity of the investigation. About of these questions were of the 'multiple choice' kind. The answers of the questions comprised four-point rating scales for response. The four-indicate rating scale was chosen to prevent the occurrence of key trend error.

A typical example of the questions related to an internal disturbance is, Over the final 12 months, how frequently did y'all observe 'absence' in your organization? (4 = often, 3 = sometimes, 2 = rarely, and 1 = never). A typical example of the questions related to an external disturbance is, To what extent does 'skilled labor shortage' impede your concern functioning (profit/growth)? (four = to groovy extent, 3 = to some extent, two = a little amount, and 1 = not at all). A typical example of the questions related to a risk indicator is, Over the last 12 months, how ofttimes did yous find 'lower than expected productivity'? (iv = often, 3 = sometimes, 2 = rarely, and 1 = never).

The questionnaires were designed in such a style that they were like shooting fish in a barrel to empathize and answer. They were pretested and carried out in ii sequential stages. The first phase consisted of a review past a console of academic experts and survey specialists who ensured that all necessary questions were included and cryptic questions eliminated, and the categorization of the questions was set up properly to ensure that subsequent data analysis would provide the desired information. The second stage was a airplane pilot report with ten participating SMEs. The responses from the pilot written report allowed the authors to verify whether respondents were biased towards certain categories of questions or leaving questions unanswered. The report establish that all respondents answered all questions and the responses on the ordinal scales were reasonably dispersed. Finally, the measuring scales were tested to verify the reliability of instrument with the assist of Cronbach's alpha (α) (Hinton [2004]; Blackness [1999]). The values of α were 0.701 and 0.716, and 0.721 for the questions of internal and external disturbances, and risk indicators (consequential effect), respectively, that ensured the reliability and internal consistency of the measuring scales.

Characteristics of studied SMEs

The significance of the SME sector in New Zealand has been increasing, with farther opportunities presented by globalization and technological development (Ministry of Economic Development [2004]). New Zealand is a small nation state of four.3 million people, ethnically various, with a potent civilization of cocky-help and independence underpinning business evolution (Ministry of Economical Development [2004]). New Zealand's size means that by international standards, its small-scale businesses are very pocket-sized simply are the dominant sector in terms of employment, organizational structure, and social and economical cohesion. A contempo report on SMEs states that in the context of policy consideration, the characteristics of small-sized businesses should typically include personal ownership and management, few specialist managerial staff, and not being part of a larger business enterprise (Ministry of Economic Development [2003]). SMEs in New Zealand typically exhibit these characteristics, and information technology is in this context that our research has been designed to deal with companies with employment in the range of x to 100 employees (Islam [2008]).

The list of SMEs selected for the mail survey and case studies was compiled from a variety of business organization databases; these were randomly chosen to represent a range of manufacturing groups. These groups covered the four sectors of (ane) metal-based product and equipment manufacturers, (2) wood and wood-based production manufacturers, (three) newspaper- and plastic-based product manufacturers, and (four) textile and garment manufacturers. These groups were selected considering of their economic importance to New Zealand. The characteristics of the participating SMEs in the mail survey are presented in Table ane.

Key findings and analysis

The key findings are categorized and presented in the post-obit sections:

Risk indicators

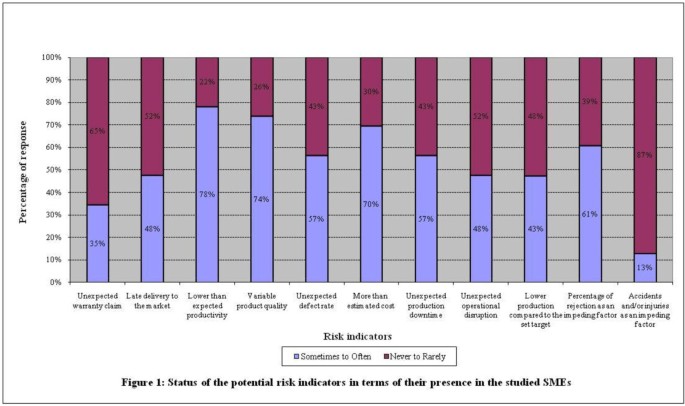

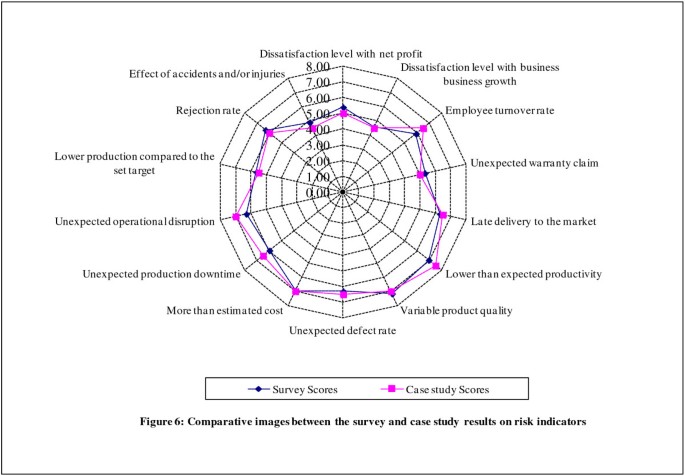

2 principal measures of corporate performance are profit charge per unit and growth rate (Freel [2000]; Geroski and Machin [1992]; Wynarczyk and Thwaites [1996]). Needless to say, there are a number of ways to measure growth rate and profitability which are substantially linked to several variables of operational activities. Several studies take overwhelmingly indicated that constructive employee direction, along with other strategic measures, tin can lead to a competitive advantage in the form of a motivated workforce, improved operational and business organisation performance, reduced employee turnover, and improved productivity, which in plow improve the net profit of a business firm (Batt [2002]; Macduffie [1995]; Virdi [2005]). Moreover, growth of a business would appear to play an important role in its sustainability in a dynamic business (Barbara et al. [2000]). Nosotros could, therefore, interpret that dissatisfaction with net turn a profit and in business growth (assuming that the business plan is realistic), equally well as meaning employee turnover rates, could be the results of inappropriate or inadequate strategic resource allotment and utilization of resource and that these should exist treated as primary indicators of potential problems for an organization. Our research approach, however, was not to verify the measures of these categories. Rather, it tried to identify whether at that place is any correlation between business growth rate and cyberspace turn a profit, and the potential disturbances. The enquiry finds that approximately 32% of the SMEs are dissatisfied with their existing 'net turn a profit' (of which ten% are very dissatisfied) and almost 40% are dissatisfied with 'business organization growth' (of which ten% are very dissatisfied). On the other hand, 9% of the organizations are very satisfied with both net profit and business organization growth. The report also finds that 30% of SMEs consider the existing 'employee turnover rate' every bit a substantial impediment to constructive business operation, while 43% signal the impediment from this factor to be small, and 26% signal it to be negligible. These are obviously linked to operational risks of straight or indirect losses due to failures in systems, processes, and people or from external factors. Thus, dissatisfaction level with internet profit and in business growth and employee turnover rate is considered as 'risk indicators' for our enquiry. In addition to these three, 11 risk indicators which are linked to operational, occupational, and economic losses are identified from the study.Figure one shows the relative position of these risk indicators in terms of their emergence in the systems of the studied SMEs.

Status of the potential run a risk indicators in terms of their presence in the studied SMEs.

Operational disturbances

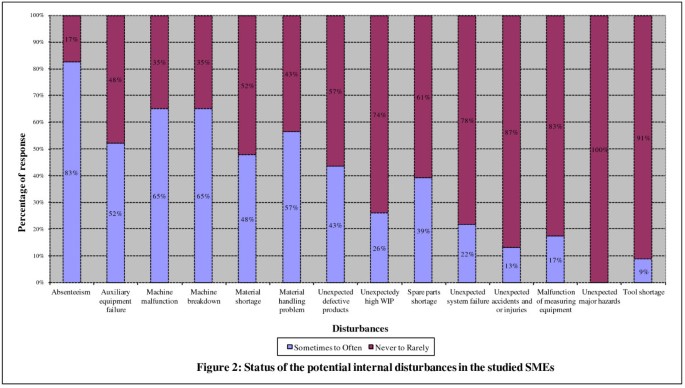

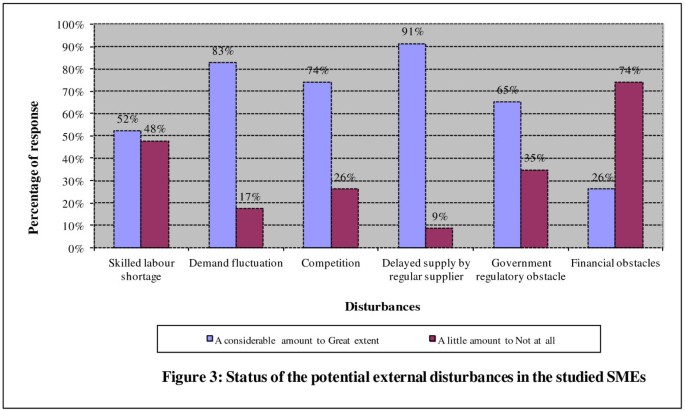

The risk indicators accept potential linkages with day-to-twenty-four hours operational disturbances, which degrade business performance and the business organization surround. In consequence, the disturbances ultimately play a vital role in putting an arrangement at risk in terms of product, safety, and financial, resulting from both internal and external customer dissatisfaction (Islam [2008]). These can lead to a loss of market share and eventually put the organization out of business organization, if they are not carefully treated. For this, a thorough investigation was conducted to identify primal operational disturbances (in essence, driving risk factors) and their linkage to some gamble indicators discussed in the previous department. We take identified a number of notable internal and external operational disturbances, which are summarized in Figures ii and 3.

Status of the potential internal disturbances in the studied SMEs.

Status of the potential external disturbances in the studied SMEs.

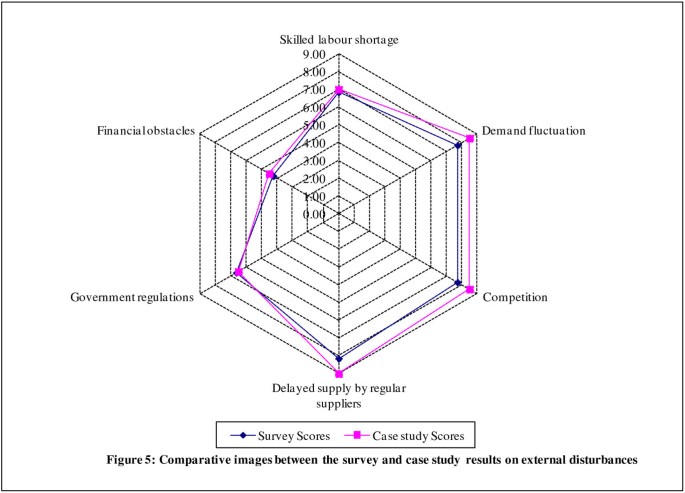

Amid the internal disturbances, absenteeism, motorcar malfunction, machine breakdown, and material handling disruption were found to be the about significant disturbances, and unexpected major hazards, unexpected accidents/injuries, and tool shortage were plant to be the least pregnant ones, while the other disturbances were found to autumn between these extremes. Amid the external disturbances, competition, delayed supply by the regular supplier, and skilled labor shortage were found to be the most significant ones, while financial obstruction was found to exist the least pregnant in terms of their influence on the operational system. However, despite the minimal influence of some disturbances, they were still considered for further analysis to find out their consequential effects.

Risk determinants

All disturbances presented in Figures 2 and 3 were considered for further analysis to determine whether they should be treated every bit run a risk determinants. The analysis included some statistical methods of parametric and non-parametric testing such every bit t test the Friedman test, and the Spearman correlation coefficient tests (Hinton [2004]) at two significant levels: α = 0.01 (99% confidence level) and α = 0.05 (95% conviction level). The results of the t test are presented in Table 2.

On the footing of their comparative occurrence in practice, the disturbances are assigned with relative scores. The disturbance which occurs most frequently is assigned with the highest score, while the disturbance which occurs to the lowest degree often is assigned with the lowest score. Thus, among the internal disturbances, 'absenteeism' scores the highest number of points, and 'tool shortage' and 'unexpected major hazard' jointly score the lowest.

The relative positions of the internal disturbances, based on their scores, are shown in the second cavalcade of Table iii. The final examination results (based on Spearman'southward correlation coefficient, r southward ) confirm the positive correlation between internal disturbances and adventure indicators; the results are presented in Table 4. Based on the positive correlation of disturbances with a number of risk indicators, scoring is performed. The highest scorer is correlated with a maximum number of risk indicators, while the everyman one is correlated with a minimum number of risk indicators. Thus, all disturbances are assigned with scores and are presented in the third column of Tabular array iii. Finally, on the basis of the production of two scores (one for appearance or occurrence and the other for correlation), final ranking is performed for the gamble determinants. The determinant which scores the maximum value is assigned with the highest rank (1), and the determinant which scores the minimum value is assigned with the lowest rank (14). Accordingly, the relative ranking for all risk determinants is established and is shown in the 5th column of Tabular array 3. According to the final ranking, 'absenteeism' becomes the most important (number ane) risk determinant amidst the internal disturbances, while 'malfunctions of measuring equipment' becomes the least of import one. Similar tests were conducted and relative measures were performed on the external disturbances, the results of which are summarized in the second and third columns of Table 5.

Discussion and evaluation

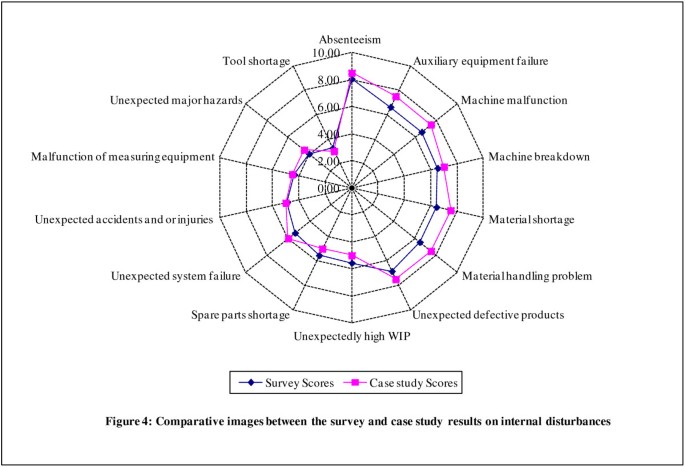

The findings from the mail survey have been presented in the previous section. Most of the findings have strongly been supported by the findings from example studies. Both investigations confirm that there are some typical internal and external operational disturbances, which expose SMEs to operational risks. Comparative findings from the two investigations are depicted in Figures 4 and five. The comparison for disturbances is made on an extended calibration of i to ten in terms of their frequency of occurrence (for internal disturbances) and of their detrimental furnishings on operational operation (for external disturbances). Figure 4 shows that both investigations identify 'absence' as the most frequently occurring internal disturbance and 'tool shortage' as the least frequently occurring in the SMEs studied, while the others autumn betwixt these two extremes. Figure 5 shows that 'delayed supply by regular suppliers' (very closely followed past 'need fluctuation' and 'contest') is the most detrimental external disturbance, and 'financial obstacles' is the least detrimental to the SMEs. Both investigations further confirmed a set of risk indicators, which can be used as the consequential effects resulting from the disturbances (Figure six). These risk indicators are linked to operational, occupational, and economic losses. The findings of both investigations once more converge on the same conclusions, in terms of the overall ranking of the disturbances, fifty-fifty though there are slight, statistically insignificant variations in some cases.

Comparative images between the survey and example study results on internal disturbances.

Comparative images between the survey and case study results on external disturbances.

Comparative images betwixt the survey and case study results on risk indicators.

The research study reveals that SMEs accept, in full general, inadequate measures and planned strategies in place to deal with such gamble determinants. Thus, the identified gear up of internal and external risk determinants found from this study will play a vital role in ensuring that SMEs realize the strengths and weaknesses in their ability to cope with the identified internal factors, as well every bit the threats and opportunities arising from the identified external factors, while assisting them in formulating and implementing strategic measures to deal with the resulting operational risks. It is obvious that some disturbances are more than detrimental than others. Moreover, the nature of the disturbance is found to be dynamic and idiosyncratic in nature. The dynamic behavior of a disturbance in different organizational settings and in different fourth dimension frame leads us to a common agreement that the appearance of a particular disturbance varies from system to system and time to time. Moreover, the same disturbance produces unlike consequential effects to different organizations based on its time of occurrence and the duration of its existence in the system. An arrangement, therefore, needs to identify the characteristics of the various disturbances and their consequential effects over time, to develop a proactive strategy for managing operational risks.

Conclusions

An organization is basically a behemothic network of interconnected nodes. Changes in ane role of an organization can affect other parts of the arrangement with surprising and often negative consequences. The minimization of delays in the system generally becomes an of import issue in lean manufacturing. In this context, the optimization of response fourth dimension to changes in the external environment becomes vital. At the aforementioned fourth dimension, smooth and consistent operational performance in the internal surround is necessary to go along the business in this dynamic business world. Internal and external disturbances to its day-to-day operation put an SME at risk in terms of production, safety, and the business itself. The risks associated with disturbances can be detected by analyzing the negative or detrimental consequential furnishings, which are identified as hazard indicators in the inquiry. We take identified some typical internal and external operational disturbances that demand to be considered as risk determinants for SMEs. It is constitute that some disturbances are positively correlated with a greater number of risk indicators and some with a lesser number of indicators. It is besides constitute that every disturbance is significantly correlated with at least one of the risk indicators. This means that in terms of operational risks, an SME needs to consider all the identified disturbances (risk determinants) in its strategic decisions for managing operational risks successfully.

We find that the majority of the studied SMEs exercise non take systematic risk management strategies in identify. It is discovered that the majority of SMEs used standard take a chance identification forms, which comply with the requirements of the Health and Safety in Employment Deed in New Zealand (Avery [1993]). The current practices in SMEs regarding risk identification relies, virtually exclusively, on the documented records of industrial injuries which these forms produce. Near misses are not generally recorded fifty-fifty though this is a requirement of the legislation. Moreover, the identification of root causes of the chance determinants and their related origins is not practiced in the studied SMEs, and in SMEs where it is expert to some extent, the flow of information tends to miss many of the relevant personnel. In addition, the disturbance handling systems in these organizations, in terms of data collection, information processing, information sharing, and determination making, are plant to be relatively weak and very informal. With regard to the identification of external disturbances, most SMEs do not accept assessment criteria in place to measure out the consequences, nor have enough information bachelor to assist them make up one's mind their root causes.

The identified gear up of internal and external risk determinants should provide a quick reference or benchmark for SMEs. The struggle with the identification of operational hazard determinants should be minimized by the identified set of determinants, obtained from a representative sample of SMEs in New Zealand. Information technology is, however, relevant to note that the relative rankings of the identified risk determinants could vary from organization to organization based on their likelihood of occurrence and their bear upon on business performance. The individual business setting, including current strategic measures, practices, and vulnerability, would play a vital role in developing appropriate strategic plans and actions in each instance. While it may be necessary for organizations to add or delete determinants to those identified in this research, depending on their detail situation, they should be able to utilize the described methodology to assist them in identifying the chance determinants appropriate to them. In this manner, they should be able to identify the extent of the risks associated with the determinants by incorporating the metrics of fourth dimension, coin, and nugget loss due to these. In conclusion, the inquiry findings presented in this newspaper will, hopefully, add together to the torso of knowledge on proficient practices in risk management resulting from operational disturbances which can affect SMEs and that may also be useful to both management professionals and researchers in the field of risk management.

Authors' information

Dr. MAI is an associate professor in the Department of Industrial and Production Engineering science, Shahjalal Academy of Science and Technology. He obtained his PhD degree from the University of Auckland, New Zealand, and has been actively doing research for more than xiii years. His principal research activities are in the areas of engineering science management including take chances management, quality management, and productivity improvement of manufacturing systems. Dr. DT is an associate professor in Technology Management at the Academy of Auckland. He gained his PhD degree from the Queens University of Belfast and has been a practicing researcher for over 36 years. Equally a chartered engineer (C. Eng) and a member of the Establishment of Engineering and Technology (IET), his master enquiry activities are in the areas of manufacturing systems and technology management. He has been consulting widely with manufacturing and procedure industries in New Zealand, Australia, and the UK in areas direct related to productivity improvement and process optimization

References

-

Anderson RL, Dunkelberg JS: Entrepreneurship: starting a new business. Harper and Row, New York; 1990.

-

Andrews JD, Moss TR: Reliability and risk cess. 2d edition. Professional Technology, London; 2002.

-

Avery Chiliad: Wellness & rubber laws at work: key issues. Teemay Consultants, New Zealand; 1993.

-

Bahr NJ: Organization prophylactic applied science and gamble assessment: a practical arroyo. Taylor & Francis, Washington, DC; 1997.

-

Barbara JO, Sandy HS, Allan LR: Performance, house size, and management problem solving. Journal of Small Business organisation Management 2000,38(4):42–58.

-

Batt R: Managing customer services: human resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth. Academy of Direction Journal 2002, 45: 587–597. ten.2307/3069383

-

Black TR: Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: an integrated arroyo to research design, measurement and statistics. Sage, G Oaks; 1999.

-

Bowman C, Ambrosini V: Using unmarried respondents in strategy research. British Journal of Management 1997, 8: 119–131. 10.1111/1467-8551.0045

-

Brewer J, Hunter A: Foundation of multi-method research: synthesizing styles. Sage, Thousand Oaks; 2006.

-

Charmaz K: Amalgam grounded theory - a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage, Thousand Oaks; 2006.

-

Dennis WJ: Raising response rates in mail surveys of pocket-size concern owners results of an experiment. Journal of Small Business Management 2003,41(iii):287–295.

-

Denzin NK: The enquiry human activity: a theoretical introduction to sociological method. 3rd edition. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs; 1989.

-

Freel MS: Do pocket-size innovating firms outperform not-innovators? Small Business Economics 2000,fourteen(3):195–210. x.1023/A:1008100206266

-

Geroski P, Machin S: Do innovating firms outperform non-innovators? Business Strategy Review Summer 1992, 3: 79–xc. 10.1111/j.1467-8616.1992.tb00030.x

-

Gibson B, Cassar G: Longitudinal analysis of relationships between planning and performance in small firms. Small Business Economic science 2005,25(3):207–222. 10.1007/s11187-003-6458-4

-

Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The discovery of grounded theory - strategies for qualitative enquiry, 11th printing. Aldine, New York; 1980.

-

Hartcher J, Allan H, Scott H: Perceptions of risks and take a chance management in modest firms. Small Enterprise Inquiry: The Journal of SEAANZ 2003,11(2):71–92. x.5172/ser.11.2.71

-

Hinton PR: Statistics explained. 2nd edition. Routledge, New York; 2004.

-

Hoffman G, Milady P, Bessant J, Perren L: Pocket-size firms' R&D, technology and innovation in the UK: a literature review. Technovation 1998,18(1):39–55. 10.1016/S0166-4972(97)00102-8

-

Islam MA: Adventure direction in modest and medium-sized manufacturing organisation in New Zealand. The University of Auckland, ; 2008.

-

Islam MA, Tedford JD, Haemmerle E: Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Management and Innovation and Engineering science, Singapore. In Strategic take a chance management arroyo for pocket-sized and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs)—a theoretical framework. 2nd edition. Singapore, IEEE; 2006:694–694.

-

Islam MA, Tedford JD, Haemmerle E: Managing operational risks in pocket-size- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) engaged in manufacturing–an integrated approach. International Journal of Applied science, Policy and Direction 2008,eight(4):420–441. 10.1504/IJTPM.2008.020167

-

Jeynes J: Risk management: ten principles. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford; 2002.

-

Jick TD: Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly 1979, 24: 602–610. 10.2307/2392366

-

Khan FI, Abbasi SA: Techniques and methodologies for risk analysis in chemic process industries. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Procedure Industries 1998, 11: 261–277. ten.1016/S0950-4230(97)00051-X

-

Luis EQ, Felisa MC, Serge W, Christopher OB: A methodology for formulating a business strategy in manufacturing firms. International Journal of Product Economics 1999, 60–61: 87–94.

-

Macduffie JP: Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and flexible product systems in the globe motorcar industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 1995, 48: 197–221. 10.2307/2524483

-

Martie-Louise V: Strategy-making process and business firm functioning in small firms. Journal of Direction and Arrangement 2006, 12: 209–222. 10.5172/jmo.2006.12.3.209

-

Milan J: An cess of risk and condom in civil aviation. Journal of Air Transport Management 2000, 6: 43–50. ten.1016/S0969-6997(99)00021-6

-

Mills J, Platts Thousand, Gregory M: A framework for the design of manufacturing strategy process: a contingency approach. International Journal of Operations and Product Management 1995,15(4):17–49. x.1108/01443579510083596

-

Ministry building of Economic Evolution: SMEs in New Zealand: structure and dynamics. Ministry building of Economic Development, Wellington; 2003.

-

Ministry of Economic Development: SMEs in New Zealand: structure and dynamics. Ministry of Economic Development and Statistics New Zealand, Wellington; 2004.

-

Mitala A, Pennathurb A: Advanced technologies and humans in manufacturing workplaces: an interdependent relationship. International Periodical of Industrial Ergonomic 2004, 33: 295–313. 10.1016/j.ergon.2003.10.002

-

Monica PB, John RW: HEDOMS—man errors and disturbance occurrence in manufacturing systems: toward the development of an analytical framework. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing 1999,9(i):87–104. ten.1002/(SICI)1520-6564(199924)9:1<87::AID-HFM5>3.0.CO;two-2

-

Monostori Fifty, Szelke Due east, Kadar B: Management of changes and disturbances in manufacturing systems. Almanac Reviews in Control 1998, 22: 85–97.

-

Mushtaq F, Chung PWH: A systematic Hazop process for batch processes, and its application to pipeless plants. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2000, xiii: 41–48. 10.1016/S0950-4230(99)00054-vi

-

Pearson AM, Dutson TR: HACCP in meat, poultry and fish processing. Blackie Academic and Professional, New York; 1995.

-

Pettigrew AM, Whipp R, Rosenfeld R: Competitiveness and the management of strategic change process: a research agenda. In The competitiveness of European industry: country, policies and company strategies. Edited by: Francis A, Tharakan Thousand. Routledge, London; 1989:36.

-

Scudder GD, Colina CA: A review and classification of empirical research in operations management. Journal of Operations Management 1998, xvi: 91–101. 10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00008-ix

-

Seastroma JW, Peercy RL, Johnson GW, Sotnikov BJ, Brukhanov North: Take a chance direction in international manned infinite programme operations. Acta Astronautica 2004, 54: 273–279. x.1016/S0094-5765(02)00301-half dozen

-

Strupczewski A: Accident risks in nuclear-power plants. Applied Energy 2003, 75: 79–86. ten.1016/S0306-2619(03)00021-7

-

Tixier J, Dusserre Thousand, Salvi O, Gaston D: Review of 62 risk analysis methodologies of industrial plants. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2002, 15: 291–303. 10.1016/S0950-4230(02)00008-6

-

Toulouse G: Accident risks in disturbance recovery in an automatic batch-product system. Homo Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing 2002,12(iv):383–406. x.1002/hfm.10020

-

Virdi AA: Risk direction among SMEs–executive report of discovery research. The Consultation and Research Centre of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London; 2005.

-

Waring A, Glendon AI: Managing risk: critical issues for survival and success into the 21st century. 1st edition. International Thomson Concern, London; 1998.

-

Watson ML, Vuuren JJ: Entrepreneurship training for emerging SMEs in South Africa. Journal of Minor Business Management 2002,40(2):154–161. 10.1111/1540-627X.00047

-

Wynarczyk P, Thwaites A: The fiscal performance of innovative small firms in the UK. In New engineering science based firms in the 1990s. 11th edition. Edited by: Oakey R. Paul Chapman, London; 1996.

-

Yin RK: Instance study research. second edition. Sage, London; 1994.

-

Zacharakis AL, Meyer GD, DeCastro J: Differing perceptions of new venture failure: a matched exploratory study of venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business organization Management 1999,37(three):1–14.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional data

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Dr. MAI designed the research, nerveless and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Dr. DT substantially contributed to the conception and blueprint stage, modification of the questionnaires and analysis, and editing of the manuscript critically for its intellectual content. Both authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary cloth

40092_2010_9_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Key questions in the questionnaire for tiptop management and middle and front-line direction. (Doc 61 kb) (Medico 61 KB)

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution ii.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Islam, A., Tedford, D. Chance determinants of small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) - an exploratory study in New Zealand. J Ind Eng Int 8, 12 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-712X-8-12

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-712X-eight-12

Keywords

- SMEs

- disturbance

- Risk

- Risk determinants

- Strategic risk management

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/2251-712X-8-12

0 Response to "Reviews of Small to Medium Sized Manufacturing Enterprises Usa"

Post a Comment